Last week, I caught up with an old friend over coffee. He runs a mid-sized manufacturing company – been at it for over 20 years. Somewhere between our talk about the current global political environment and how crazy the tariff imposed by the US, he said, “I got this email from a young entrepreneur asking if I’d consider selling. Said he’s running a ‘search fund.’ Should I take it seriously?”

If you’ve never heard of a search fund, you’re not alone. But if you’re a business owner, especially in Southeast Asia, this might be something worth paying attention to.

Let’s break it down.

What is a Search Fund, Really?

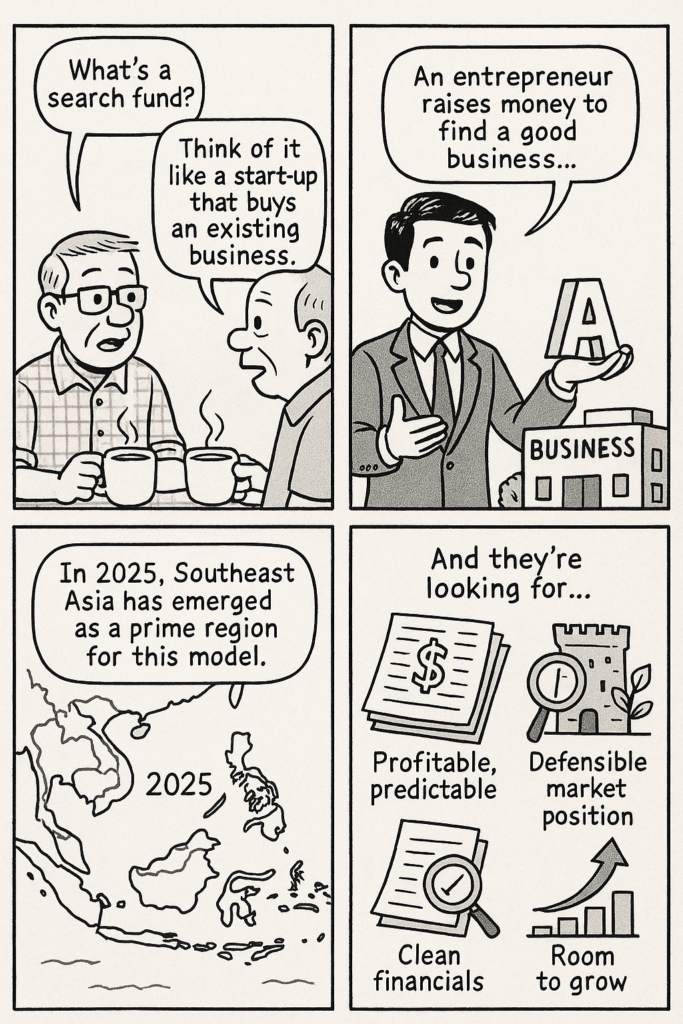

Think of it as a different kind of startup – not one building a new app or product, but one where the goal is to find a great business, buy it, and run it for the long haul.

Typically, someone or a group of people (usually an ivy-league MBA graduate or seasoned operator with solid experience) raises some money from investors to fund a “search” for a good, stable business to acquire. Once they find the right one, they raise more money from the same backers (and maybe a few new ones) to buy the company and step in as CEO.

It’s not about flipping the company. It’s not about making drastic changes. It’s about long-term value, responsible ownership, and continuity.

And in 2025, Southeast Asia has quietly become one of the most exciting regions for this model. The timing makes sense as many business owners are thinking about succession. Retirement is on the horizon, but legacy still matters.

What Are These Search Funds Looking For?

Let me walk you through what they’re typically evaluating, based on conversations I’ve had with several searchers, investors, and former sellers:

1. A Profitable, Predictable Business

Searchers are drawn to businesses with stable, recurring revenue and healthy margins. They’re not chasing hypergrowth or the next big tech disruption. They want something steady. Ideally, you’ve been EBITDA-positive for a few years, and the numbers make sense even in a slower economy.

It’s the kind of business that might fly under the radar, quietly successful, built on relationships, and delivering consistent value.

2. A Defensible Position in the Market

In a layman way, this means your business has something that’s hard to replicate. Maybe it’s long-term contracts or good relationships with long term suppliers/customers. Maybe it’s a niche product or regulatory licenses that others can’t easily get. Maybe it’s a rock-solid reputation built over decades.

They’re not necessarily looking for cutting-edge innovation. They’d rather have a strong moat than a shiny new toy.

3. Clean Financials and Transparent Operations

This is the non-negotiable. Investors backing these funds are serious people – they want clean books, clear records, and no unpleasant surprises. You don’t need to have a Big Four audit, but your numbers should hold up under scrutiny.

Think of it like selling your house. It doesn’t need marble floors, but the plumbing/piping better work.

4. Room to Grow.

Search funds love businesses that are already solid but have clear, achievable paths for improvement. Maybe your marketing has been old-school, or you have not been streamlining your processes with technology or you haven’t fully tapped into regional markets. That’s the exact key points these Search Funds are looking for. What they don’t want is a turnaround project with toxic culture, debt issues, or broken systems.

A good foundation with room to scale, that’s the sweet spot.

Why Southeast Asia? Why Now?

In 2025, there’s a strong tailwind. Especially with the uncertainty in Trump’s Tariff move, SEA market is large enough to self-sustain.

While many SME founders are nearing retirement and succession is a growing concern. Meanwhile, a new wave of entrepreneurial talent is returning from global business schools, eager to lead. Investors are also warming up to search funds as a viable alternative asset class.

Combine these forces, and you get a region ripe for this kind of ownership transition.

Should you consider a Search Fund Buyer?

If you’re a business owner who:

- Is profitable but getting tired of day-to-day operations.

- Wants to preserve the legacy of what you’ve built.

- Is open to transitioning leadership over time

…then yes, it’s worth having the conversation. Not every inquiry will be the right fit, and not every searcher will be ready. But the right match can be a win-win.

I’ve seen it happen—a friend sold his logistics company to a search fund operator two years ago. Today, he sits on the board, the new CEO is growing the business, and he finally got to spend more time with his family without worrying about payroll. Plus, if the company becomes large enough and goes to IPO/acquired, he still made a very handsome return.